Artist’s Note

“Between that earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out. I did not say my prayers that night: here, I felt, what would be would be.” —Willa Cather, My Ántonia (1918)

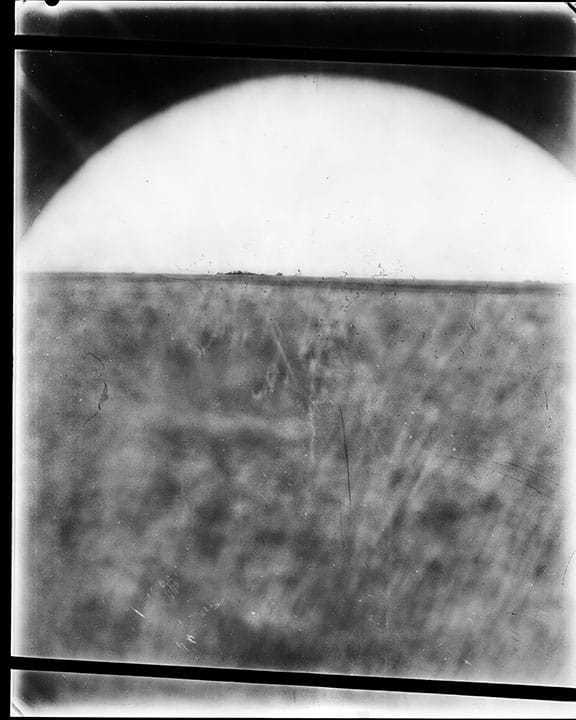

On February 11th, 2009, I was diagnosed with HIV. Looking for a healthy way to process this flood of emotion, I took to my camera. What started out as self-portraits, soon morphed into landscapes. I saw myself in the Great Plains of Nebraska, anchored to the land, bending with the wind instead of against it—the winds of home. During this conversation between the landscape, the camera, the film, and myself, I realized that the doubt and negativity surrounding my diagnosis were carried away in the images. Now, each time I lift the homemade cap from the barrel lens something happens: the old landscape, ratified as a state in 1867, and the lens, made that same year, reunite. Now, these ancestral plains—five generations—evoke a sense of belonging, of completion. HOME is a body of work that celebrates who I am and where I come from.

When photographing, I let my intuition guide the way. It usually leads me to an isolated subject sitting on the prairie, towering above the waving grass. Then, the real magic happens: the ten second exposure. The wind, which never stops blowing, moves and jostles the camera during the long exposure, creating ghost-like blurs and waves of undefined areas. Instead of traditional apertures found in modern cameras, I use water stops, the edges of which come into view and vignette the images. These aesthetic choices make it seem like those Great Plains go on forever and touch the edge of existence. Ultimately, the blurred grass and softened edges allow our minds to wander into another realm where we commune with our ancestors, bridging past with present and future. This communion has built a stronger appreciation for not always being in control, that beauty can come from chaos—a life lesson I take with me in all aspects.